Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Describe the main issues patients experience wearing masks and understanding masked speakers.

- Explain the main strategies people report using to overcome difficulties understanding masked speech.

- Identify differences by region, age, and hearing status.

Introduction

Globally, the coronavirus pandemic (Covid-19) has resulted in a variety of rules and restrictions in the interest of public safety. Restrictions have included the use of masks in public spaces, reductions in personal meeting gathering size, and lockdown conditions. At a country and regional level, there are differences in the degree and timing of these restrictions. For example, in Chicago, CHI, the use of masks was introduced in August 2020, and in Copenhagen, Denmark, it was in October 2020.

Covid-19 restrictions have impacted communication. One example is an increased use of masks, which impact communication by eliminating speechreading cues and muffling the acoustic signal (Corey et al., 2021). These problems are greater in noisy situations (Toscano & Toscano, 2021, Naylor et al., 2020). Additionally, mandated, and voluntary lockdown conditions have resulted in fewer face-to-face interactions and an increase in the use of phone and video interactions for social connection and the delivery of health services (Jimenez-Rodriguez et al., 2020).

Several studies have specifically investigated the consequences of Covid-19 restrictions for people with and without hearing loss. Saunders et al. (2021a) found that people with hearing loss were significantly more impacted by masking than those without hearing loss and that the use of masks had far-reaching consequences for individuals, impacting interpersonal connection and willingness to engage in conversations in addition to impacting communication. Naylor et al. (2020) investigated the impact of Covid-19 on hearing impaired people and found that people with worse hearing (WH) were more anxious about communicating with masks as compared to people with better hearing (BH) (categories of hearing are based on self-reported hearing difficulty.) WH participants also indicated more relief, than BH participants, about not being obligated to attend social events where they might hear poorly. Studies by Saunders et al. (2021a) and Naylor et al. (2020) were conducted in the UK in 2020. These studies had very limited older participants; Saunders et al. (2021a) included 11 people 80 years and older and the oldest participant in the Naylor et al. (2020) study was 76 years old. Given the rapidly changing nature of Covid-19 and the global impact, there is a need to explore experiences of Covid-19 over time and with people of all ages and from different geographic regions. It is also relevant to explore the impact of COVID-19 on a larger population of hearing-impaired people including older adults.

Since the studies by Naylor et al. (2020) and Saunders et al. (2021a) were conducted, Covid-19 has surged resulting in increased restrictions in many places. In the present study, we sought to follow-up and expand on the study by Naylor et al. (2020), by examining the impact of Covid-19 on hearing impaired people during February 2021 – a time when Covid-19 infection rates and restrictions were at their peak – for people living in the greater Copenhagen, Denmark (CPH) metropolitan area and the greater Chicago, Illinois (CHI) metropolitan area. The study aimed to include a large sample of older adults, so to better understand the experiences of older adults with hearing loss during Covid-19.

Methods

Design

A rapid online survey methodology was employed to obtain a timely snapshot of the situation. This approach has been used by other groups during Covid-19 (e.g., Geldsetzer 2020; Naylor et al., 2020; Zhong et al. 2020).

Participants

Participants were recruited from the CPH and CHI GN Hearing test persons database. The participants in this database are volunteers who have agreed to be contacted to participate in a variety of studies. The data is privatized using a randomized number and password protected key. All data was maintained according to the General Data Protection Regulation EU standards. Participants were not compensated for participation.

We aimed to recruit at least 100 people into the study with at least 25 people over 80 years. The survey was sent via email to 382 people in CPH and 134 people in CHI. In total, 294 people responded to the survey giving an overall response rate of 56.7%. Two-hundred-thirty participants were from CPH and 64 were from CHI, giving a response rate by region of 60% and 48%, respectively. Participants’ ages ranged from 28 to 95 years (M = 71 years) in CPH and from 56 to 93 years (M = 74 years) in CHI. Moreover, 60 participants were 80 and over, 46 participants (18%) in CPH and 14 participants (21%) in CHI.

Materials

The survey design was guided by previous Covid-19 and hearing loss surveys (see Saunders et al., 2021a and Naylor et al., 2020). It was revised and updated using a fast iterative process as survey results were time sensitive. The initial draft was developed by the three authors and was reviewed by two hearing impaired persons (over 70 years of age) and four audiologists to ensure questions were comprehensible. After revisions were made, the final version of the survey was translated into Danish and then reviewed by two native Danish speakers. The survey was then translated back to English to ensure the meaning was unchanged.

The final survey contained 24 questions (see appendix 1). Eighteen were fixed quantitative responses and six were open-response questions. Questions asked about self-reported hearing ability and hearing aid use, tinnitus, and the use of face masks and communication behaviors during Covid-19. Most of the quantitative responses were on a 5-point Likert Scale, where participants could respond how much they ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’ with a statement and included ‘not applicable/not sure’. Three of the six open-response questions gathered additional information to quantitative questions and three were specifically related to experiences with conversations using masks/at distance. The survey was administered online using SurveyMonkey®. Supplementary data on participants’ age was gathered through the GN Hearing Database.

Procedure

At the time of the survey, similar mandatory public health restrictions were in place in Copenhagen and Chicago, although rules in Chicago were stricter. The restrictions at the time the surveys were completed included wearing masks in shops, public transport, restaurants, medical appointments, and other crowded places. Masks were required for children over 2 years old in Chicago, while in Copenhagen only people over 12 years old were required to wear masks. An email invitation was sent on February 5th, 2021, to participants in Copenhagen and on February 26th, 2021, to participants in Chicago. Given the initial response rate in both regions, only one round of invitations was sent.

Data Analysis

Questions were grouped into one of five themes: hearing and hearing aids; tinnitus; behaviors; communication; and emotions. Descriptive statistics report the overall findings from the quantitative survey questions and qualitative questions were analyzed using content analysis. Open-ended questions in Danish were translated to English by the authors and all responses were then analyzed in English. Next, subgroup comparisons were examined for hearing status, region, and age.

For hearing status, participants were divided into better hearing (BH) and worse hearing (WH) subgroups based on self-rated hearing ability. Participants reporting hearing as ‘very poor’ or ‘poor’ were assigned to WH group and participants reporting hearing as ‘average’, ‘good’, or ‘very good’ were assigned to the BH group. For region, CPH responses were compared to CHI responses. For age, participants under 80 years were compared to participants 80 and over.

The questions that included a 5-point Likert scale were collapsed into positive (top two responses), neutral (middle response), and negative (bottom two responses). Questions were analyzed calculating the frequency of top, middle, and bottom responses. Responses of ‘Not applicable/unsure’ were removed from the analysis. Chi-squared testing were done on the contrast between the three subgroups using a 3x2 cross-tabulation of responses. P values (set at .01) are reported without correction.

Results

Hearing and hearing aids (Questions 1-7)

Survey questions 1 to 7 related to participants hearing status, use of hearing aids. Of the 294 participants, 229 (77.9%) self-reported their hearing as being “poor” or “very poor”, thus were assigned to the WH group. Sixty-five participants (22.1%) reported hearing was “average”, “good” or “very good” and thus were assigned to the BH group. Regarding hearing aid use, 38 participants (6.1%) reported not using hearing aids, eighteen participants (12.9%) used one hearing aid and 238 participants (80.9%) used two hearing aids. The most common style of hearing aid was the receiver-in-ear device, with 176 participants (71%), behind-the-ear hearing aids were used by 53 participants (11.9%) and custom hearing aids were used by 18 participants (7.7%). Participants were also asked about their hearing with hearing aids, 152 participants (61%) described their hearing as “good” or “very good” with a hearing aid, 100 participants (31.5%) described hearing as “average” with hearing aids and 20 participants (8%) described their hearing as “bad” or “very bad” with hearing aids.

For daily use time, 201 people (79.4%) reported using hearing aids more than 8 hours, 17 (6.7%) reported using between 4-8 hours, 18 (7.1%) reported using for 1-4 hours, 9 people (3.6%) reported less than one hour per day and 8 people (3.1%) had not used their hearing aids. Participants were asked if they had reduced their hearing aid use time during Covid-19. Most, 201 participants (77%) disagreed. Thirty-eight people (15%) agreed that they used their hearing aids less than before Covid-19, and nineteen people (7.5%) were neutral. This question was followed by an open-ended question asking why they had/had not changed their hearing aid use. For people who reported using their hearing aids less, they indicated doing so because they were spending more time at home alone and communicating less. For example, one participant who wore their hearing aids less wrote ‘A lot fewer opportunities to be together with others. No theater/concerts. Situations where I get great benefit of my hearing aids’ (CPH ID 211). In contrast, people who indicated no reduction in hearing aid use explained no change because they needed their hearing aids. ‘I hear audio books, watch tv, set the alarm when cooking. Without hearing aids, I cannot hear when the egg is done, and it is cumbersome to hear audio books, tv in Danish is hopeless.’ (CPH ID 121)

Tinnitus (Questions 11 & 12)

Two questions related to tinnitus. The first, asked if participants sometimes, always, or never experienced tinnitus and 112 respondents (44.8%) reported they did not experience tinnitus. The remaining 56.6% of participants were then asked if their tinnitus had become worse since Covid-19. Only 8 participants (5.7%) indicated that their tinnitus had become worse since Covid-19, 78 participants (55.7%) disagreed and 54 (38.6%) were neutral.

Communication (14-16)

Three questions asked participants about their experiences communicating with people wearing a mask and at distance. Most people (42.6%) agreed that it was difficult or sometimes difficult (41%) to understand people when they spoke to them with a mask. Only 43 people (16%) said that it was never difficult. When responding to the question about the difficulty understanding speech when people spoke at the recommended safe distance of 2 meters (6 ft), 40 participants (14.3%) disagreed that understanding speech at the safe distance was difficult, 171 participants were neutral, and 154 people (55.2%) agreed that it was always difficult. Four themes emerged from the open-ended questions about the difficulty that occurs when someone talks with a mask or at a distance. Themes are: no lipreading, sound distorted by mask, speaker does not make accommodations, and distance to talker.

The most common reason cited for difficulty understanding speech at distance or when the speaker was wearing a mask was that lipreading was not possible. Some respondents’ answers indicate awareness of the importance of lipreading for their speech understanding, however others’ responses showed surprise at how important lipreading was for speech understanding, “It has come to my attention how much I use lip reading. When my hearing is not supported by that, more gets lost.” (CPH ID 461).

Speech sounds distorted by mask. Respondents also commonly commented on the distorted audio mostly described as muffled in English and woolen (ulden) in Danish. “The speech becomes more woolen. Loses nuances.” (CPH ID 199)

Speaker not making appropriate accommodations. Participants reported some speakers did not speak loud enough, spoke too fast or had an accent, making understanding difficult. As written by one participant “It all depends on the speaker!...” (CHI ID 656) “

Distance to talker. Distance was cited by relatively few people but captured responses where social distancing impacted communication: “Due to social distancing, you can't lean in close to hear better.” (CHI ID 618)

Behavior (13, 19-21 & 23)

Five questions asked about participants’ behavior during Covid-19. One question related to the number of conversations with people wearing a mask in the previous week. There were two open-ended questions. One asked, “In which way do you communicate differently (if you do) when you wear a face mask?” The other asked, is there anything you do to alleviate the difficulties that can occur when someone talks to you with a mask on or keeps distance? There were also two questions related to use of phone calls or video calls.

Regarding the number of conversations had in the previous week with people wearing a mask, 40.7% (118) reported daily conversations with people wearing masks, 29% (84) reported two to six conversations per week and 30.3% (88) reported having fewer than two conversations per week with someone wearing a mask.

Content analysis yielded the same themes for the two open-ended questions, as such findings are combined. Three themes emerged from the analysis related to communicating with a mask or at distance.

Taking action. ‘Ask them to slow down or repeat or speak louder. I'm not bashful about it.’ (CHI ID 652). The first theme ‘taking action’, captures active strategies people used to optimize and overcome communication difficulties. For example, people reported wearing hearing aids, informing the person they were speaking with of their difficulty understanding and/or of their hearing loss. Asking the speaker to adjust his/her communication by speaking slower, louder, more clearly and/or for repetition, or having a family member interpret what they missed.

Doing nothing. 'There is really nothing you can do ...’ (CPH ID 308). Many people reported that they did nothing because they did not perceive any difficulty communicating with a mask or at distance or because they did not know of any strategy to help. Some simply reported they had not changed their behavior with no explanation. For example, one respondent wrote ‘more or less the same’ (CPH ID 471). For this response, and other similar responses, it is unclear if communicating as usual works well, or no change is made because they do not know of any strategies that might be helpful.

Avoidance. Many respondents also reported that since Covid-19 they see fewer people and have fewer interactions, such that this theme related to people who avoided social interactions. For example, one individual responded, 'I do not see people these days, sadly.' (CPH ID 248).

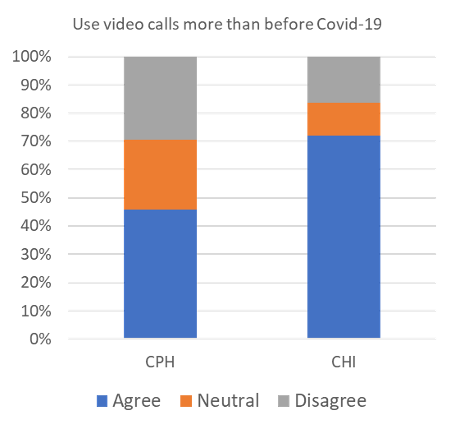

Finally, behaviors related to phone and video phone conversations showed that half of the respondents reported that they had used videos calls more since Covid-19 and a third reported that they had made more phone calls than usual. See figure 1.

Figure 1. Summary of response proportions for the change in telephone use (left) and video call use (right) since Covid-19.

Emotions (8-10, 17, 18 & 22)

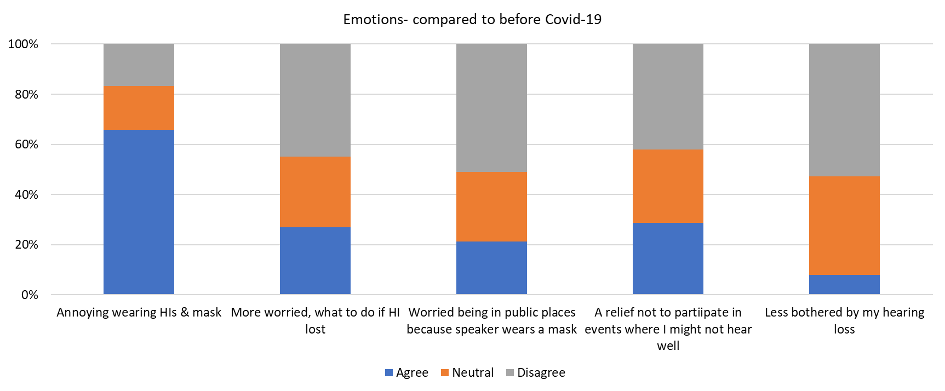

Six questions asked participants about their emotional reactions to Covid-19. The five quantitative questions assessed: annoyance of wearing hearing aids and a mask, worry about what to do if they had a problem with their hearing aids, worry communicating in public spaces with masks and at distance, relief not having to participate in social get-togethers where they might not hear well, and how bothered participants were by their hearing loss now compared to before Covid-19. Results for these questions are shown in Figure 2. One quarter of participants reported that they were worried about what to do if they lost their hearing aids or if they stopped working. A fifth of participants reported that they were worried about communicating in public spaces with masking/distancing. Less than ten percent of participants were less bothered by their hearing loss now than before Covid-19. A fourth of participants indicated that they were relieved not to be required to attend social get-togethers where they might hear poorly.

Figure 2. Response proportions for quantitative questions related to emotions.

The final question relating to emotions was a free-text question, that followed up people’s response to annoyance, asking those who reported annoyance wearing a mask and hearing aids why it was annoying. Most people were annoyed about wearing hearing aids and explained it was annoying because of practical issues (hearing aids get tangled in mask) or from fear of losing their hearing aids. ‘When I put the mask on, the hearing aids pop off. If I put on the mask first, it is difficult to get the hearing aid wire over my ear in a way that it is secure.’ (CHI ID 616) A few people reported acoustical concerns such as sound of breathing being louder and mask interfering with sound of hearing aids.

Sub-group comparison: Hearing Status

In total there were 294 participants, 65 BH (22.1%) and 229 WH (77.9%). There were significant differences in response proportions between BH and WH participants for three themes: hearing and hearing aids, communication, and emotions. No significant differences in responses were seen for tinnitus and behaviors. Table 2 in the appendix shows the survey responses for the quantitative questions for the BH and WH groups.

Hearing and hearing aids (Questions 1-7)

There was a significant difference comparing BH and WH groups for hearing aid use. In the WH group 90% reported wearing two hearing aids compared to 49.2% in the BH group X2 (2, N=294) = 57.7, p<.000. Significantly fewer people in the WH group described their hearing as good with hearing aids, 56.3% compared to 84.2% in the BH group, X2 (2, N=251) = 11.2, p=.004. Additionally, participants in the WH group used their hearing aids significantly more per day compared to people in the BH group. For WH participants, 90.6% reported wearing their hearing aids for more than 4 hours per day, compared to 61.5% of BH participants, X2 (2, N=253) = 29.9, p<.000. Finally, more people in the BH group (41%) reported using their hearing aids less since Covid-19 as compared to people in the WH group (10.3%), X2 (2, N=250) = 28.33, p<.001.

Communication (14-16)

Significantly more WH participants reported it was always difficult understanding speech when the speaker is wearing a mask compared to BH participants, with 49% of WH participants and 15.7% of BH participants reporting this, X2 (2, N=263) = 28.22, p<.001. They also agreed significantly more of the time that it was difficult to understand the speaker at distance, X2 (2, N=279) = 19.67, p<.001.

Emotions (8-10, 17, 18 & 22)

WH participants were significantly more worried, than BH participants, about needing to communicate with someone wearing a mask in a public place. A fourth (25.7%) of WH participants reported being worried while only 6.3% of BH participants reported this, X2 (2, N=282) = 12.3, p=.002. Similarly, one in three people with WH agreed that they were relieved not to have to participate in social get-togethers where they might not hear well, while only one in ten people with BH reported this, X2 (2, N=282) = 13.4, p=.001. Finally, it was significantly more common for people with WH (76.6%) to disagree that they were less bothered by their hearing loss now as compared to before Covid-19 compared to people with BH (34.5%), X2 (2, N=273) = 9.9, p=.007.

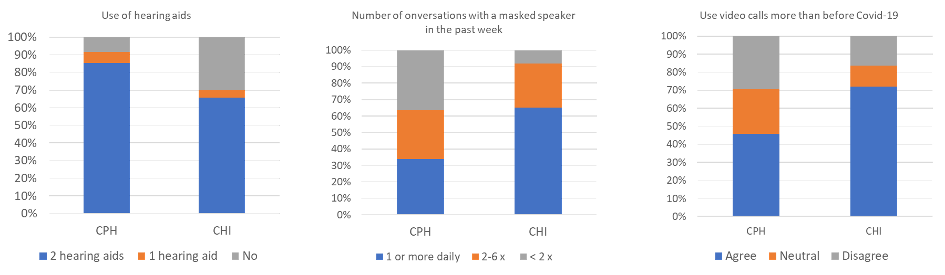

Sub-group comparison: Region

In CPH, 230 people responded to the survey; in the CHI 64 participants responded. Responses differed significantly by region for use of hearing aids, numbers of conversations with a masked speaker, and use of video calls during Covid-19 (see Figure 3). More people in CPH reported owning hearing aids (91.7%) compared to people in CHI (70.3%), X2 (2, N=294) = 20.43, p<.000. Some of this might be explained by the fact that more people in CPH reported WH (81.3%) compared to in the CHI (65.6%), this difference was not significant X2 (2, N=294) = 6.27, p=.012.

People in the CHI reported having significantly more conversations with masks per day compared to people in CPH, 65.1% of people in the CHI indicated conversations at least once per day with someone wearing a mask compared to 33.9% of people in CPH, X2 (2, N=290) = 25.2, p<.000.

Figure 3. Self-reported responses showing significant regional differences. Hearing aid use (left), number of conversations with someone wearing a mask (middle), and use of video calls since covid-19 (right).

Finally, people in the CHI were more likely to report that they had increased their use of video calls since Covid-19 (72.1%) compared to people in CPH (45.9%) reporting increased use X2 (2, N=255) = 12.9, p=.002.

Sub-group comparison: Age

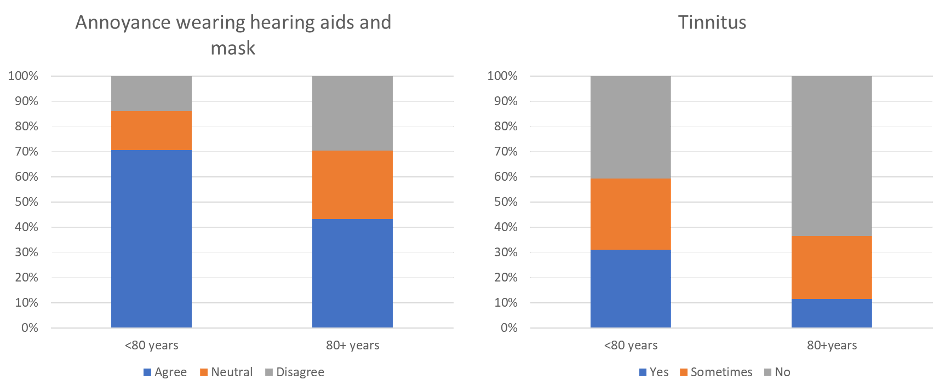

By age, 241 people under 80 years and 53 people 80 and over participated in the study. Two questions showed significant differences by age. People 80 and over were less likely to experience tinnitus as compared to under 80-year-olds, X2(2, N = 250) = 9.5, p = .009.

People 80 and over were also significantly less bothered by wearing hearing aids and a mask compared to people under 80 years, X2(2, N = 251) = 12.3, p = .002. (Figure 4). Open-ended question asking participants to explain why they experienced annoyance with wearing a mask and hearing aids was only asked of participants experiencing annoyance, so a better understanding of reasons for not experiencing annoyance among cannot be explored. Reasons for annoyance, among those reporting annoyance with masks and hearing aids were similar for older and younger participants.

Figure 4. Self-reported annoyance to wearing a mask and hearing aids by age subgroup (left) and experience with tinnitus (right).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of people living with hearing loss during Covid-19. Survey findings were grouped in one of five themes related to hearing and hearing aid use, tinnitus, communication, behaviour, and emotions. Descriptive statistics showed a high proportion of people using hearing aids, that hearing aid use had not typically been reduced during Covid-19, and that people are not less bothered by the hearing loss during Covid-19. Very few people who experience tinnitus report that it had worsened since Covid-19. Around one in four people were worried about social interactions in public where the speaker was masked or a distance and around one in four people reported relief not to have to go to social events (which were cancelled due to Covid-19) where they might hear poorly. Sub-group analysis demonstrated that hearing status yielded more differences in responses as compared to region and age.

Hearing Status

By hearing status, it was clear that the experiences of Covid-19 differed in terms of behaviour, communication, emotions, and overall impact; people with WH experienced more difficulties communicating with masks and over distance and a greater emotional impact from Covid-19 compared to people with BH. These findings are unsurprising and align with other recent Covid-19 studies by Naylor et al. (2020) and Saunders et al. (2021a) as well as audiology literature that has long identified the psychosocial consequences of self-perceived hearing difficulty on communication and well-being (see Vercammen, Bott, & Saunders et al., 2021b). It was heartening, that many people reported advocating for themselves, explaining to the person they were speaking with that they had hearing difficulties. Stigma related to one’s own hearing loss has long been documented in research; however, our findings suggest that many people were comfortable alerting people to their hearing difficulties to help overcome the additional communication burden from wearing a mask/communicating at distance.

This survey is a follow up to the survey by Naylor et al. (2020) and 13 of the 24 questions were the same or very similar in both studies, see appendix 1. Overall, our findings are consistent with that of Naylor et al. (2020) and there are only a few differences observed. Regarding the latter, Naylor et al. (2020) found no significant difference between BH and WH participants regarding understanding speech with masks or at a distance, in this study, WH participants reported significantly more difficulty. Also, while people with WH are significantly more likely to agree that masking increases anxiety about going to public places in both studies, the proportion reporting this anxiety was higher in the study by Naylor et al. (2020) with 60.3% of people with WH and 32% of people with BH report anxiety as compared to 25.7% of people with WH and 6.3% of people with BH in the current study reporting anxiety. We speculate the differences described, might, in part, be due to participants in the current study having more experience with speaking to people wearing masks and at a distance as our survey was completed 9 months after the study by Naylor et al. (2020).

A similarity between the studies is that both showed greater reduction in use time for BH than WH participants. However, overall reductions in use time were reported by many more participants in the study by Naylor et al. (2020) where 61.5% BH and 26.8% WH reported using hearing aids less compared to 41% BH and 10.3% WH in the current study. Possibly, reduction in hearing aid use is more obvious when Covid-19 restrictions were quite new or there may be other reasons for these differences such a greater proportion of older participants in the current study. Younger people of working age might be sent home from work possibly resulting in more change to daily routines for younger people and a greater reduction in hearing aid use time.

Region

Generally, few differences are observed by region in the current study. The significant differences were self-reported hearing loss with a higher percentage of people in the CPH group fell in the WH group which is likely to explain at some of the fact that significantly more people in CPH reported owning hearing aids compared to people in the CHI. In CPH. Another factor that might explain higher reported hearing aid ownership in CPH is that hearing aids are provided free of charge or at reduced rate by the government in CPH, but this is not generally true in the USA/CHI.

People in the CHI reported having significantly more conversations with masks per day compared to people in CPH. This could be because masking restrictions were stricter in CHI than in CPH. In the CHI masking was required for people over two years of age and for all public interactions, while in CPH, only people over 12 years old needed to wear masks and the requirements were mainly for indoors in CPH whereas they also applied at least in some cases outside in the CHI. It could also be because people in the CHI had a higher number of conversations with people in public. This study does not offer any explanations for this difference.

Finally, people in the CHI were more likely to report that they had increased their use of video calls since Covid-19. A similar increase in video calls, as seen in the CHI, was seen in the study by Naylor et al. (2020) with around 75% agreeing that they had increased video calls during Covid-19. Since we did not ask about actual amount of video calls before and current amount, it could be that CPH and CHI respondents are now having the same number of video calls because people in CPH were already having more video calls before Covid-19. A general increase in video calls and other digital technologies for health care, education and many other purposes have been reported worldwide during Covid-19 (Jiménez-Rodríguez et al. 2020, Vargo et al. 2021). Denmark Statistic Database (Danmarks Statistik, 2021) reports a remarkable increase in video- and audio calls via suppliers like FaceTime, Skype, Messenger etc. from 2019 to 2020 (56% to 70%). The same increase is not seen in the numbers so far from 2020 to 2021 (70% to 73%).

Age

Recent surveys of adults living with hearing loss during Covid-19 identified a participant bias, in that adults over 80 years of age were typically underrepresented among participants (Naylor et al., 2020; Saunders et al., 2021a). As such, we aimed to include at least 25 people 80 years and over in our study. Despite having almost 20% of the sample being 80 years or older, only two questions yielded differences in participant responses by age. A possible reason that few differences in responses for different age groups could be due to a bias for tech savvy older participants, in the present study all participants had enough technology knowledge and cognitive capacity to complete the survey online. Differences may occur if a paper survey was provided to participants as well (Kelfve et al., 2020).

The two questions that did yield differences in responses by age, showed that adults 80 years and over were less annoyed to wear hearing aids and a mask compared to adults under 80 years and experienced less tinnitus. For the former question, qualitatively, there was no difference in open-ended responses by age. It could be that older people were more concerned with being infected with Covid-19 as compared to younger adults (Schou-Bredal et al., 2021) and therefore prioritized safety-measures over practical annoyances. Regarding the latter question on tinnitus prevalence, this finding differs from population-based studies that typically show there is no significant difference in proportion of people experiencing tinnitus by age (Oosterloo et al 2021; Sindhusake et al., 2003). Methods differ in the present study to those in Oosterloo et al. (2021) and Sinduhsake et al. (2003), which may contribute to the difference in findings.

Tinnitus

Overall, findings in the present study tend to contradict previous research related to tinnitus and Covid-19. As discussed above, there was a difference in tinnitus by age, with fewer people over 80 years experiencing tinnitus as compared to people under 80 years. Additionally, relatively few people in the present study reported experiencing tinnitus and of those who did, most reported it was unchanged. This finding differs from previous research that has indicated tinnitus has worsened during Covid-19 for those people who have tinnitus and Covid-19 (Beukes et al., 2020). In the present study, we did not ask participants whether they had contracted Covid-19, such that we cannot compare our findings to that of Beukes et al. (2020), who found that people who had 40% of people who had Covid-19 symptoms experienced worse tinnitus.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength in our study is the method of developing the survey (rapid survey). It allowed us to carry out the investigation as things were happening/while mask wearing was required. Another strength of this study is that two geographical areas were covered at the same time, allowing for investigating any differences in experiences across continents.

Furthermore, the study included a sizable group of older adults to giving a better understanding this group’s experiences with Covid-19. This was particularly relevant as older people are more vulnerable to Covid-19 and are overrepresented among people with hearing loss. Also, we saw a high response rate to our survey with 56.6% of invited participants completing the survey. Other studies carried out also during Covid-19 show response rates of around 40% (Naylor et al., 2020; Kelfve et al., 2020).

A potential weakness of the current study is that test participants come from a potentially biased sample, as they have all committed to being part of a test panel for hearing aids and can commute to a test facility. They are therefore possibly more open to talking about their experiences with hearing loss and hearing aids and this may differ from the general population of people with hearing loss. However, their experiences with communication with hearing loss and masks is expected to be similar to their peers.

Conclusion

This study found people with WH had a different experience with Covid-19 than people with BH. WH reported more difficulty with masked speech and distancing and more relief at not having to attend events where hearing might be difficult. Few regional differences and differences by age were observed, showing that hearing was the dominant influence on the results of the current survey. Compared to the previous study by Naylor et al. (2020), which was conducted at an earlier phase in the pandemic, there are more differences between BH and WH for masked speech understanding and understanding speech at a distance, this is possibly due to more experience with these situations. This greater experience might also explain the reduced anxiety speaking to people with masks as seen in both BH and WH in the current study compared to the previous study. It might be interesting to explore this change to better understand what causes reduction in anxiety about communication for hearing impaired people.

References

Beukes, E. W., Baguley, D. M., Jacquemin, L., Lourenco, M. P. C. G., Allen, P. M., Onozuka, J., Manchaiah, V. (2020). Changes in Tinnitus Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 592878–592878. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.592878

Corey, R., Jones, U. & Singer, A. (2020). Acoustic effects of medical, cloth, and transparent face masks on speech signals. The Journal of Acoustical Society of America, 148(4), 2371-2375. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0002279

Danmarks Statistik (2021) https://www.statistikbanken.dk/BEBRIT09

Geldsetzer, P. (2020) Knowledge and Perceptions of COVID-19 Among the General Public in the United States and the United Kingdom: A Cross-sectional Online Survey. American College of Physicians Public Health Emergency Collection, published online 2020 Mar. DOI: 10.7326/M20-0912

Jiménez-Rodríguez D, Santillán García A, Montoro Robles J, Rodríguez Salvador MdM, Muñoz Ronda FJ, Arrogante O. Increase in Video Consultations During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Healthcare Professionals’ Perceptions about Their Implementation and Adequate Management. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(14):5112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145112

Kelfve, S., Kivi, M., Johansson, B., & Lindwall, M. (2020). Going web or staying paper? The use of web-surveys among older people. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20(1), 252–252. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01138-0

Naylor, G., Burke, L., Holman, J. (2020) Covid-19 Lockdown Affects Hearing Disability and Handicap in Diverse Ways: A Rapid Online Survey Study. Ear and Hearing, 41(6):1442-1449. DOI: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000948.

Oosterloo, B. C., Croll, P. H., de Jong, R., Ikram, M. K., & Goedegebure, A. (2021). Prevalence of Tinnitus in an Aging Population and Its Relation to Age and Hearing Loss. Otolaryngology-head and neck surgery: official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 164(4), 859–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820957296

Saunders, G. H. Jackson, I. R. & Visram, A. S. (2021a) Impacts of face coverings on communication: an indirect impact of COVID-19, International Journal of Audiology, 60:7, 495-506, https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1851401

Saunders, G., Vercammen, C., Timmer, B., Singh, G., Pelosi, A., Meis, M., Launer, S., Kramer, S., Gagné, J., & Bott, A. (2021b). Changing the narrative for hearing health in the broader context of healthy living: a call to action. International Journal of Audiology, 60:sup2, 86-91, https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2021.1905892

Schou-Bredal, I., Skogstad, L., Grimholt, T. K., Bonsaksen, T., Ekeberg, Øivind, & Heir, T. (2021). Concerns in the Norwegian population during the initial lockdown due to the covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 6119. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18116119

Sindhusake, D., Mitchell, P., Newall, P., Golding, M., Rochtchina, E., & Rubin, G. (2003). Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus in older adults: the Blue Mountains Hearing Study. International Journal of Audiology, 42(5), 289–294. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992020309078348

Toscano, J. & Toscano, C. (2021). Effects of face masks on speech recognition in multi-talker babble noise. PLOS ONE, 16(2), eCollection. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246842

Vargo D, Zhu L, Benwell B, Yan Z. (2021) Digital technology use during COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid review. Human Behavior & Emerging Technologies, 3:13-24. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.242

Vercammen, C., Bott, A., & Saunders, G.H. (2021) Hearing health in the broader context of healthy living and well-being: changing the narrative, International Journal of Audiology, 60:sup2, 1-3, https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2021.1905893

Zhong, B. L., Luo, W., Li, H. M., Zhang, Q. Q., Liu, X. G., Li, W. T., & Li, Y. (2020). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. International journal of biological sciences, 16(10), 1745–1752. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.45221

Appendix

Table 1.

Survey question | Conditions | Answer options |

1. How is your hearing when you don’t use hearing aids?* | None | Very good Good Average Poor Very poor |

2. Do you use HAs?* | None | No I use two hearing aids I use one hearing aid |

3. Which type of HA(s) do you use? | Conditioned by yes to HA use | BTE RIE In-the-ear Cochlear implant/other |

4. How is your hearing when you use HAs? | Conditioned by yes to HA use | Very good Good Average Poor Very poor |

5. On an average day during the last week, how many hours did you wear HAs?* | Conditioned by yes to HA use | I have not used them Under one hour per day 1-4 hours per day 4-8 hours per day More than 8 hours per day |

6. During Covid-19 I have used my HAs less than I usually do?* | Conditioned by yes to HA use | Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree |

7. Why? | None | Free text field |

8. It is annoying to wear HAs as well as a face mask* | Conditioned by yes to HA use | Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree |

9. Please explain why it is annoying to have both hearing aids and a face mask on | Conditioned by strongly agree or agree to annoyance | Free text field |

10. I am more worried now than before Covid-19, about what to do if I have a problem with my HAs or if I lose them? * | Conditioned by yes to HA use | Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree |

11. Do you suffer from tinnitus? | None | Yes, often Sometimes No |

12. My tinnitus has gotten worse during Covid-19?* | Conditioned by yes to tinnitus | Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree |

13. How many conversations have you had over the past week where the speaker was wearing a face mask? | None | No conversations the past week 1-2 conversations per week 3-6 conversations per week At least once per day Most of the day most days |

14. It is hard to understand speech when the person I am speaking with is wearing a mask (if you use hearing aids, please answer when listening with hearing aids)* | None | Always Most of the time Sometimes Rarely Never Don’t know/not relevant |

15. What makes it difficult to understand speech when the speaker is wearing a face mask? Describe the difficulties you experience | None | Free text field |

16. When people speak to me at the recommended distance (6 feet) it is difficult to hear and understand them* | None | Always Most of the time Sometimes Rarely Never Don’t know/not relevant |

17. It worries me to be in public places (e.g., the supermarket) because I might have to speak to someone with a face mask? * | None | Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree |

18. It is a relief not to have to participate in social get-togethers where I might not hear very well* | None | Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree |

19. In which way do you communicate differently when you are wearing a face mask? | None | Free text field |

20. I use the telephone more now than I did before Covid-19 | None | Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree Don’t know/not relevant |

21. I use video calls now more than I did before Covid-19* | None | Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree Don’t know/not relevant |

22. I am less bothered by my hearing loss now than before covid-19* | None | Strongly agree Agree Neither agree nor disagree Disagree Strongly disagree Don’t know/not relevant |

23. Is there anything you do to make it easier to speak to someone wearing a face mask or who is at a distance? | None | Free text field |

24. Any other comments? | None | Free text field |

* Question is same or very similar as in Naylor’s study.

Table 2. Survey responses for quantitative questions by self-reported hearing status.

Survey question | N | Better Hearing (BH) | N | Worse Hearing (WH) | p- value | ||||

(%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | ||||

2. Do you use HAs? |

65 | Yes, 2 49.2 | Yes, 1 12.3 | No 38.5 |

229 | Yes, 2 90 | Yes, 1 4.4 | No 5.7 |

<.001 |

3. Which type of HA |

38 | BTE 7.9 | RIE 81.6 | Custom 10.5 |

210 | BTE 23.8 | RIE 69 | Custom 7.1 |

.082 |

4. How is your hearing when you use HAs? |

38 | Good 84.2 | Average 15.8 | Bad 0 |

213 | Good 56.3 | Average 34.3 | Bad 9.4 |

.004 |

5. On an average day during the last week, how many hours did you wear HAs? |

39 | >4hrs/ day 61.5 | 1-4hrs/ day 12.8 | <1hr/ day

25.6 |

214 | >4hrs/ day 90.6

| 1-4hrs/ day 6.1 | <1hr/ day

3.3 |

<.001 |

6. During Covid-19 I have used my HAs less than I usually do? |

39 | Agree 41 | Neutral 12.8 | Disagree 46.1 |

214 | Agree 10.3 | Neutral 6.5 | Disagree 83.2 |

<.001 |

8. It is annoying to wear HAs as well as a face mask? |

39 | Agree 59 | Neutral 25.6 | Disagree 15.4 |

212 | Agree 67 | Neutral 16 | Disagree 17 |

.349 |

10. I am more worried now than before Covid-19, about what to do if I have a problem with my HAs or if I lose them? |

39 | Agree

33.3 | Neutral

25.6 | Disagree

41 |

213 | Agree

25.8 | Neutral

28.6 | Disagree

45.5 |

.624 |

11. Do you suffer from tinnitus? |

38 | Yes

29 | Sometimes

15.8 | No

55.3 |

212 | Yes

27.4 | Sometimes

29.7 | No

42.9 |

.184 |

12. My tinnitus has gotten worse during Covid-19? |

18 | Agree 0 | Neutral 27.8 | Disagree 72.2 |

122 | Agree 6.6 | Neutral 40.2 | Disagree 53.3 |

.245 |

13. How many conversations have you had over the past week where the speaker was wearing a face mask? |

64 | At least 1 per day

45.3 | 2-6 per week

28.1 | < 2 per week

26.6 |

226 | At least 1 per day 39.4 | 2-6 per week

29.2 | < 2 per week

31.4 |

.658 |

14. It is hard to understand speech when the person I am speaking with is wearing a mask |

51 | Always

15.7 | Sometimes

47.1 | Never

37.3 |

212 | Always

49.1 | Sometimes

39.6 | Never

11.3 |

<.001 |

16. When people speak to me at the recommended distance (6 feet) it is difficult to hear and understand them. |

61 | Agree

31.1 | Neutral

42.6 | Disagree

26.2 |

218 | Agree

61.9

| Neutral

27.1 | Disagree

11 |

<.001 |

17. It worries me to be in public places (e.g. the supermarket) because I might have to speak to someone with a face mask? |

64 | Agree 6.3

| Neutral 28.1 | Disagree 65.6 |

222 | Agree 25.7 | Neutral 27.5 | Disagree 46.8

|

.002 |

18. It is a relief not to have to participate in social get-togethers where I might not hear very well. |

64 | Agree 10.4 | Neutral 32.8 | Disagree 56.3 |

222 | Agree 32.9 | Neutral 28.4 | Disagree 37.8 |

.001 |

20. I use the telephone more now than I did before Covid-19 |

62 | Agree 32.3 | Neutral 33.9 | Disagree 33.9 |

215 | Agree 32.6 | Neutral 39.1

| Disagree 28.4 |

.658 |

21. I use video calls now more than I did before Covid-19 |

57 | Agree 61.4 | Neutral 15.8 | Disagree 22.8 |

198 | Agree 49.5 | Neutral 23.2 | Disagree 27.3 |

.262 |

22. I am less bothered by my hearing loss now than before Covid-19 |

58 | Agree 10.3 | Neutral 55.2 | Disagree 34.5 |

215 | Agree 7.4

| Neutral 34.8 | Disagree 57.6

|

.007 |

Percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding errors. Counts (n) are excluding ‘N/A’ responses. ‘Agree’ is the sum of ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ responses, ‘Disagree’ is the sum of ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’ responses. HA = hearing aid; BTE = behind-the-ear; RIE = receiver-in-ear. Bold identify significant differences in 3x2 chi-square proportion testing.

Citation

Sjolander, M.L., Møller, K.N. & Bott, A. (2022). Snapshot of the impact of covid-19 on people with hearing loss in Chicago, Illinois and Copenhagen, Denmark. AudiologyOnline, Article 28125. Available at www.audiologyonline.com